Hello friends! I am so happy to announce that I was accepted into Columbia’s MFA program for Creative Writing, starting this Fall! My privilege is not lost on me, and this essay reflects that a bit. I plan to continue to share on Hello Bobbie, where all my most meaningful work lives.

___

The storms this week are constant. Gusts of wind can be seen in silver swoops as it pushes the trees to one side as they simultaneously shriek and flutter their leaves. The rain patters sideways on the window and I watch it dance and drip down as I mix the pancake batter from inside the kitchen. I squint so that I may study my flower pots from afar, the ones that sit on the patio, and notice that the soil is as sopped as it gets, heavier by the minute with the downpour, likely tackier than the batter I am whisking. Will they rot? They couldn’t be this thirsty, I think to myself. These rainy conditions give me a jolt of emotions that pulse through me, starting from my neck down to my feet. The hollowness in my chest can only be compared to the absence of the sun, because it’s likely in mourning, as we all are. Thankfully nothing has changed for my children, as I hear them fighting over the coveted Tory Story cup. It is 7 in the morning and I am already overwhelmed, one of the most self defeating desires. Nonetheless I dress their pancakes with syrup and sliced strawberries and we sit to eat. My grandmother can be heard coming down the stairs, and suddenly things feel easier to manage.

The sacrifices my family have made, along with millions of others, are coming into question. Earlier this year, I wrote a piece called “Resistance” where I highlighted works from my teachers (Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and Cherríe Moraga). As my teachers constantly express, the world has always been on fire, history will always repeat itself. Colonization ensues, more present than ever before. Civilization continues to turn on eachother while the wealthy mocks us and pins us as savages. A small way to repay my teachers is to continue to write about the world that’s burning. ICE raids are happening throughout the country. I am hearing stories of how people are being taken, disappearing from sight, as if they are the subject of a magic trick gone horrifically wrong. As I reflect on the fact that I’ll be the first in my family to work towards a graduate degree, it feels timely to mention my first teacher and mentor: my grandmother.

When I was eight or nine years old, my grandmother slipped on a wet floor while holding a pot of stock she had boiling on the stovetop, causing the scalding liquid to spill onto her feet. I don't remember what she was preparing, and I don’t remember how the floor became wet in the first place, but I do remember that she barely reacted. Immediately her feet became tomato red, the bridge of her right foot already blistering and peeling, as her toes splayed out and separated, suffering from the after shock. After rushing to assess her feet, I remember looking upwards to catch a glance of her, her face hardly grimaced. She hobbled to the couch as we helped her, my sister and I, a small girl under each arm.

At the time my grandparents lived in a small apartment. The pantry overflowed with Mistolin and bulk packages of Bounty Paper towels, linen closets filled to the brim with towels and bed sheets that in order to pull one out the whole tower of tightly packed linens would collapse. You’d only need to take 3 steps to enter every public space: kitchen, dining room, and family room, the TV within arms reach of the stove. However, the small space did not account for how much they provided for us. The best part of this apartment is that it was a two minute drive from ours. Sometimes, once I learned, I’d even ride my bike there. My parents, who’d gone out for the night and deemed my grandparents their reliable babysitter, soon arrived to take her to the hospital, having to cut their social endeavors short. As she left with them she complained under her breath that there was still so much to do to get dinner on the table. Her veiny, marbled feet with blues and purples swirled throughout, now marked by white patches, the scalding liquid burning off her skin tone entirely.

When my grandmother was twenty-three years old, the revolution enveloped Cuba, disgorging it into a communist regime. The only autonomy at that point was a choice of which camp she’d work in, and she chose the farms, la agricultura. By then she was already married and my mother was born, my grandfather dropping off and picking her up from the camp everyday. The roles there varied; one day they’d tend to the citrus, plucking lemons and limes and oranges. Other days they’d spread pesticides, making most of them very sick. The hardest part for her, as she recounts this story to me, was not being with her daughter. Manual labor aside, there was a deeply rooted community in the camp. To make their shifts easier to bear, they formed a band. My grandmother had the role of the singer, an obvious decision because of her beautiful voice. Everyone else would rhythmically tap on the metal tables with spoons and sticks. Artistry is rarely about recognition, artists are the ones that make something out of nothing, the ones who drag their bodies from the contempt of their situations to still live.

In 2018 I went for a routine 8 week pregnancy appointment and was told I was miscarrying. My doctor handed me Misoprostol and I took it. As a form of comfort, my husband took me to Chipotle for lunch where we’d have to leave mid meal because the internal thrashing started a bit sooner than expected. Eventually, it would take ten hours of raging contractions to expel the dead cells inside of me. At the time, my husband and I had recently moved to an apartment in a high rise building that was surrounded by many other high rise buildings. I’d peer out my window from the 24th floor, onto a sea of gray, concrete high rises expanding my entire periphery. God looks down on us like ants on a hill.

Eventually, her and my mother appeared, both dressed in leggings and loose fitting t shirts and flip-flops, both as a sign of the times and a sign of urgency. I was still unfamiliar with where things were and I was physically unable to offer them a thing. My grandmother found a large blanket after watching me attempt some rest on our couch. She covered me up, intentionally leaving my feet exposed so that she could rub them. It was the first time in ten hours that my body felt like it was returning to me. Deep sighs, almost unanimously, heard throughout the staleness of the room. As she rubbed my feet she gave me a chance to rest. We would get up soon to eat croquetas and crema de malanga, she said. But first, she rubs my feet, the two things that carry the weight of our living, the things that allow us to move forward despite all the things that have tried to hold us back. We walk in order to fall, we get up only to fall again. None of this is very bad as long as there’s someone to help you get up. But first, there’s rest. A defiant, dignified rest.

My grandmother is the only person that gives me a powerful sense of repetition. She stands clear in all of my memories. Since I’ve been writing, I’ve learned ideas are prompted from memory. For me, an essay is paying a visit to my memories, feeling like a place I’ve always known. When I read an essay by another writer, I want to feel like I’m entering somewhere I’ve never been, perhaps a different realm. Tata, my grandmother, metonymically, is all of that for me. She is my arrival, she is where I transcend, and she is where I lay my drifted and intangible thoughts to rest safely. The irony is that she doesn't know any of this, nor that our closeness to each other is how I measure intimacy within relationships outside of her. Her existence, quite literally, the ammunition for mine. Tata the profound, a woman who exhibits the density of meaning, yet makes me my coffee and watches me sip it so that she can rinse the cup once I’m done. A real artist thrives in the shadows. If realms had a name, the one I visit would carry hers.

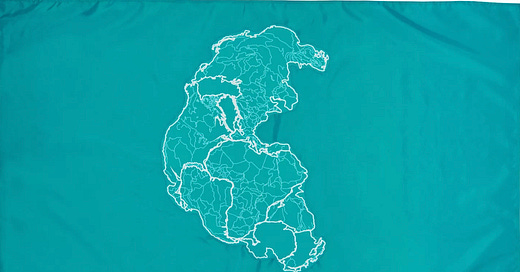

Perhaps, when my grandmother was younger, she yearned for a bigger life. Instead, she was given a life that was burdened by geography. Geography is vast and endless, yet marked by walls and barriers and political regimes. Geography is simply the hand we’re dealt, purely dumb luck. Because of the choices my family made to leave Cuba, I was born in Hialeah, FL. I am able to live a life of safety and education, and because of them, I will be the first in our family to attend graduate school. Why me? Why not her? She’s the artist, yet I’m the one who’s recognized as one. She’s raised me and is now helping me raise my sons, yet I am the one audacious enough to write about it, spewing words together and delusional enough to call it “art.” Privilege, most of the time, falls onto the wrong hands. I don’t know why I have something she never stood a chance for.

Around the same time as the foot burn, I was learning how to ride a bike. I was outside my grandparents’ apartment trying to measure how long I could ride before I’d need to plant my feet on the floor to regain equilibrium. I got too confident and went too fast and took a sharp turn I was not experienced enough to handle, which caused me to fall, the palms of my hands saving me from eating pavement.

Upon landing on my hands, I called for her and she came out in her nightgown, one patterned with light purple tulips nestled into small cavities of green grass. She came outside, my fall interrupting her time in the kitchen, I noticed her wiping her hands on her nightgown as she’s simultaneously approaching me. She crouched down to help me up, her gold chain with La Virgen tapping my forehead. Inside, she puts wet paper towels on my palms, which is when I notice the tulips now spotted with specks of blood from my scrapes. My grandfather can be heard blowing raspberries somewhere nearby.

My grandfather, a man who displayed both gentleness and stubbornness at the same time, assumed life would be fuller if he never allowed her to work or learn English. He was, more than anything else, lonely. Some men choose to devoid themselves of intimacy, and as a result, men in “control” succumb to their own self-ruin. I wonder if women quite literally carry the species, not because of our capacity to bear children, but because of our capacity to survive the emotional whippings of a man's projection. All the men in my family have left, they were everywhere but home, anxiously searching for themselves. Perhaps it was their father-wounds that didn’t allow them to find safety in the women they have chosen. It is at the same time outrageous but something that is natural to me. Yet the paradox continues to thrive, and I find myself exultant in my womanhood, in the assuredness I have of my identity outside of what is socially expected of me: I am hyper vigilant and controlled, I am complex and wild, I am constantly practicing resistance so I can savor my fundamental self. Real freedom lies in acceptance, and I think I’m almost there. Utopia is something you build slowly because it starts from the inside.

It is reaching the middle of June and the days are getting long. Daylight leaks through the slit of my curtains by 6am and doesn’t leave until after 7pm. It makes me miss 4:30pm sunsets when I could lie to my kids about the time of day and put them to bed early. Now my lying is called out instantly, “it’s not bedtime it’s playtime!” They say as they exhale abruptly and point their tiny little fingers towards my bedroom window, an aggressive reminder that it’s still daylight, a slight eye roll and raised brows on their faces to drive the point home. This is around the time I get close to reaching my daily existential crisis so I remind myself to practice a little restraint. My grandmother, seen at the foot of the door, smiling a half smile, a semblance of frivolity piercing through her eyes, perhaps enjoying the spectacle of her granddaughter's menial frustration.

“Déjenlo que son niños” she tells me. Leave them they're just kids. I walk out of my room tight-lipped, with a pink shade of embarrassment on my face.

I think a lot about the conditions that have brought me here, a woman who writes and will soon have the once unthinkable access of pursuing a masters degree in writing. At the foundation of it all, it always comes down to dumb, geographical luck. What I have learned from all of my teachers is that I have no choice but to use my conditions for my own benefit and to dedicate the work to the artists that came before me who couldn’t.

This morning is cloudless, it's blue and taut and vast. It’s impossible to absorb its limitlessness. The air is still heavy with humidity, upon walking outside my armpits react with an immediate tinge. I am barefoot because my kids stole my slippers which forces me to stand on the moist grass, practicing “grounding” against my will. I think about my smallness and fantasize about reaching largeness. I think about the things I’ll be able to produce in graduate school. I think about the mentors I’ll meet and the resources I’ll have. I think about the criticism I’ll face, both internal and external, and my tolerance for it. I think about the room of my own and what kind of writing will emerge from it, if it will change from the writing it is now. Writing seems coercive, where will it take me? Will it submit to my plan? Or will it have its way with me? I think about the artists I’ll meet and the different realms I’ll enter, and if they’ll even come close to the one who carries her name.

What a beautiful tribute. This: "Tata the profound, a woman who exhibits the density of meaning, yet makes me my coffee and watches me sip it so that she can rinse the cup once I’m done."

You're a dream. I can't wait to see how you continue to honor and unravel the fellow artists in your life.