There is something beyond beautiful to be said about childhood memories. It molds us into adulthood. It is where pride comes from. It raises you with morals. Pride for your country is like an automatic sense of benevolence. I may not know who you are, but if you are Cuban, you will always have a friend in me. But if you are Cuban then we must already know each other, tangibly unbeknownst to us, but subconsciously a bond supported by our history, our culture, our food, our loud love. Cuba is a place I’ve been raised to love but also been raised to never visit. Three generations have passed since 1959 and Cuba, to put it lightly, has aggressively declined since. The memories of Cuba that lift us up is not Cuba in its present form. We have comfortably watched a country die from afar; feeling helpless but thankful the diaspora were the lucky ones that made it out in time. At least. Until now, the Cubans on the island are protesting the economic crisis, fighting through fear and hunger, desperate for change.

Playing Domino’s with my family showed me what pride felt like. Over games is how the stories of Cuba typically began. I imagine these things have shaped me in some way. My heritage is something I carry subconsciously with me every day. Maybe it’s the azabache around my neck, and the azabache I have my son wear. Maybe it’s the prayer card I keep in my wallet. Maybe it’s the feeling of abundance that large plates of food bring. Maybe it’s the “mulas” (mules) we coordinate to send clothes and money and toys back to the island. Maybe I can make sense of how this has shaped me later in life. But right now all I can do is describe it.

I was born in Hialeah. My birthday is the same day as Fidel Castro’s. My native tongue is Spanish. I grew up on a 15-acre farm. My mouth regularly eats congri, lechón, plátanos. My eyes know how to detect a ripe avocado and mango. My ears were raised on Benny Moré, Hector Lavoe, Celia Cruz, Roberto Torres, Rey Ruiz, Willy Chirino. My nose knows when the sofrito is just right, just the perfect amount of onions, garlic, peppers, tomatoes, and sazón. My hands pulled yucca roots from the ground and set possum traps so they wouldn’t steal our chicken eggs. My hands prayed to San Lazaro and La Virgin de Guadalupe. My hands prepared rum cocktails before they even knew how to pour liquid into a glass without spilling. My bare feet ran up and down lanes of vegetation, scaring off the rabbits that sought refuge in our roots. My arms still carry scars of scratches from the roosters we’d throw into a ring to fight another. That’s how I learned to count money, from the men who’d bet on the fight. My grandfather deemed me the accountant and I’d stuff the money into the waist of my basketball shorts until the night was over and we’d count it together.

Childhood memories can come back to you like a bad dream. There were always conversations of how we’d send money back to the island, of how our Tio’s and Tia’s would travel back, strategizing different routes like going through Mexico or Haiti. There was always the underlying aura of worry. I had cousins arrive in Naples when I was a junior in high school and I’d listen to their stories. Their school schedule in Cuba was much different than mine. They attended “escuela de campo.” Their lunch was rationed and they spent the latter part of the day working the cane fields. They were only allowed to go home one day out of the week. They were hungry for big plates of food as well as new things: Dunkaroos, Lunchables, Dell computers, flip phones, Nintendo 64. They spoke of their country with much dissent. Their whole lives were stuck in a time warp, never playing with a modern plastic toy, or owning furniture that was so old it was rotted.

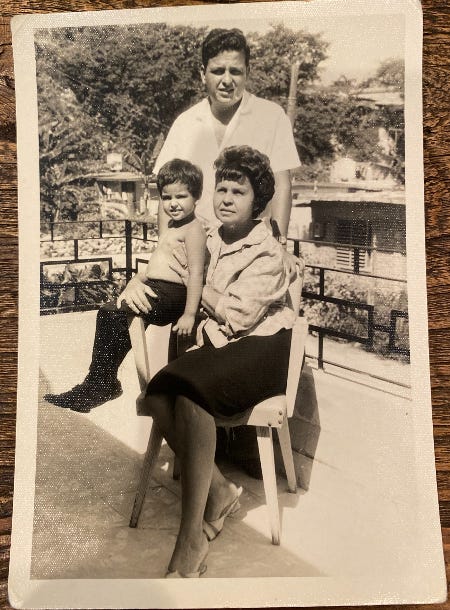

There was a family I’d never meet, or only would come to know in photos. Some are still in Cuba, completely defiant and believing in Communism. Propaganda won the battle for a few. Others not wanting to break up their family, or leave the island that they call home. Others making ground in Puerto Rico or Las Vegas or New York.

Some things were hard to make out as true. Some things I imagined could be ruled out as fables. Or at least, there was so much talking between my parents, grandparents, and extended family that it was hard to make sense of it. My dad said there was no food so our family hunted down stray dogs on the street. My grandmother said my grandfather spent years in jail for going against the government and she birthed her children alone. Provinces were affected differently: Havana was still in good shape, my tia had a big house with a flock of horses. But the family in Cienfuegos was not as lucky. People who were once educated with a career focus were plucked from their jobs to work on fields, in factories. To supply the government with what is needed to fuel communism. Men were called to aid Fidel in his government style, by becoming government aides and doing things like spreading Soviet-style propaganda.

As a girl, My family would research how to get goods and medicine to the island through agencies, only for it to take months to arrive. But, there began to be what I viewed as slivers of hope. Like when Obama opened up an embassy in Havana in 2014, when Fidel Castro died, prisoner exchanges between Cuba and the US, Cuba’s ease on travel, banking, and internet access. My Tio’s, for once, were able to travel directly from Miami to the island. But despite all this, there was still the embargo. Despite all this, there was still the Regime, and the strong grip of Russia and China. There were the false promises of reforms. My family sends money to Cuba, but not without the fear that the Regime will intercept it in some way.

I’ve never been to Cuba. To put it simply, I was always told I shouldn’t. But putting family loyalty aside, how could I want to? Perhaps this is the clutch of generational trauma making its way unto me. I was raised on the notion that Cuba, once a lush island, was now barren. My family always told me it is a place they don’t want me to see. It wasn’t until I entered adulthood that I tried to make sense of this.

My family, as they told stories, only conveyed the beauty of Cuba. They strayed from digging in too much on the Soviet-style government that forced itself onto their beautiful island. They deter from talking about how they escaped, of how my grandfather was repeatedly jailed, of how my grandmother was plucked from her house to work in “agricultura” for 6 months.

Over the course of three generations, food and medicine have become more scarce, inflation has become impossible to shop for basic goods, and the government inflates more and more tax. The island regressed into apocalyptic ruin. Amidst all this, Covid-19 hit. It’s because of this, the privileged life I live in the US, that I’ll never know the degree of suffering Cubans endure.

On Sunday, July 11th, protests in Cuba began and even seeped into big cities like Havana and Santiago. I’d like to think the massive marches and demonstrations happening now in Cuba will rattle the system in some way. The crisis of food and medicine shortages has consumed them more than their fears. On Instagram there are videos of people chanting “We want vaccines!” and “Down with dictatorship!”

Protests quickly took to Miami. On the same day, Calle Ocho was swarmed with Cubans overcome with patriotism and solidarity. Miamians took to the highways and closed down major streets. This morning I saw pictures of the protests in New York. My social media is completely flooded with awareness of the situations and prose of hope. It is an overwhelming reminder of the foundation in which we were raised; benevolence, pride, solidarity, and loud love as a result from loud suffering.

It’s hard to have Cuban pride in your blood and not let this consume you. It’s hard to understand the suffering since the past three generations of Cubans in America have not been present to experience the aggressive demise of the country. To watch a country die is not the same as dying within the country. The Cubans that live there are different than the Cuban diaspora that live free outside of the island, to be able to relish in memories because it is in their distant past. A past bountiful in avocados and mangos and tobacco and freedom and beaches and the capability of making the same mistakes over and over. My family and I are fortunate to hold different kinds of memories of Cuba. Cuba the island 90 miles south of Key West. Cuba the bountiful. The sepia-toned photographs we hold close to our hearts make it hard to compare to the Cuba we are seeing now in the media.

The beauty of being Cuban-American is being pulled more towards a country you’ve never known, more than the country you were born in. It’s seeing photos of Havana, Camagüey, Cienfuegos, and feeling like it’s a place your heart recognizes. It’s preparing a cafecito in advance of conversations with my grandmother about the memories that lift her up but that also consume her like a bad dream. The resilience lives in my blood too. It’s standing in solidarity with the people on the island, the ones willing to die for basic human rights. I am just one person among the lucky diaspora of Cubans, with my own story of how Cuba has molded me. Who are we without our pride? Without our loud love? Who are we without a chance to fight for what we are owed?

Abajo El Comunismo!

Down with Communism!

#soscuba

A straightforward breakdown of what is happening in Cuba:

Resources on where and how to donate. If there any others that you have found please send me a message!

a. Friends of Caritas Cuba: The largest donor worldwide to the most vulnerable people in Cuba. Senior citizens, the disabled, children, and persons living with HIV/AIDS. The link will take you to their PayPal

b. Cubanos Pa’lante: A community of Cuban Americans rallying to collect goods and Zelle payments for medicine and to recharge phones for Cubans on the ground coordinating support packages. Donations can be made to cubanospalante@gmail.com through Zelle.

Lastly, a message from our King:

This post was what I needed in a flood of social media posts that can make the tragedy of what’s happening in Cuba feel sad, but so far away. This story reminded me of the stories, the humanity, the families this is affecting. Thank you ❤️🇨🇺